David Lam is a Professor of Economics at the University of Michigan and Director of the Institute of Social Research. He is highly respected and widely published in the field of demography. His elected positions include being past president of the Population Association of America and being elected to the Council of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP). Lam is truly a giant in the field of demography, and deserving of all his many honors.

David Lam is a Professor of Economics at the University of Michigan and Director of the Institute of Social Research. He is highly respected and widely published in the field of demography. His elected positions include being past president of the Population Association of America and being elected to the Council of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP). Lam is truly a giant in the field of demography, and deserving of all his many honors.

Dr. Lam published an essay last year in N-IUSSP, the IUSSP’s online news magazine. Titled “The world’s next 4 billion people will differ from the previous 4 billion“, it got me riled up because I felt that Lam ignored our human life-support system–the natural world. My response, “The world in which the next 4 billion people will live“, was also published by N-IUSSP. This sparked a third, “Global population, development aspirations and fallacies” and then a fourth essay, “Thinking about the future: the four billion question”.

Here are very short abstracts of the four essays. Since I’m doing the abstracting, the abstracts may not be totally objective!

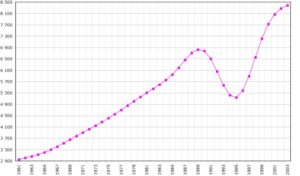

- Dr. Lam notes that it took just 50 years to add 4 billion people to give us the 7 1/2 billion we have now, but that it will take until about 2100 to add the next 4 billion–and then growth will probably stop. Much of this growth will be in Africa, and the people will be older. He also believes about this population growth “… the experience of the last 50 years gives room for optimism about the world’s ability to support it.”

- I am less optimistic, fearing that we have already used so much of the planetary resources that there will be significantly less left for those who come after us.

- Dr. George Martine feels that I am overly optimistic about the ability of family planning to slow population growth. Unfortunately, I agree with him! Martine had 4 concerns about the prior 2 articles: “a) the urgency of environmental threats; b) the recognition of diversity in ‘population’; c) the limitations of fertility reduction solutions; and, d) the urgency of redirecting ‘development’.”

- I like the way this essay starts: “The ‘population question’, central to the debate about humankind’s future since the 18th century, has slipped away from center stage and fallen into a coma in recent years.” The essay takes a critical look at some of the factors affecting population and our ability to inhabit Earth. Dr. Livi Bacci looks at climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions, and points out that it is not just population that has increased but also the financial ability of people to purchase and use carbon-based fuels–consumption.

I welcome folks to look at these four essays and draw your own conclusions. I first read Lam’s article because I am a member of the IUSSP and subscribe to N-IUSSP, but they are available online to anyone. Just search using their titles. You can even submit a response without being a member. It is good to have a debate on these subjects that are so important to our future!

Richard