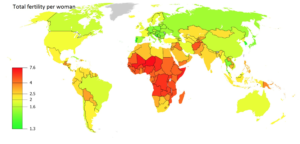

Last month I wrote about the 5 countries I have enjoyed visiting in Africa, including citing their amazingly low per capita GDP. Although most of the population growth over the next decades is predicted to occur on that continent, I see some rays of hope.

There are two places in the world where studies have been done on ways to increase voluntary family planning, along with other important medical research. One is Matlab, Bangladesh and the other is Navrongo, northern Ghana. I had never heard of the Navrongo studies until shortly before visiting there!

Both Matlab and Navrongo have shown that community health workers can improve health significantly. In addition to family planning, the Ghanaian studies studied several successful interventions, including vitamin supplementation and mosquito nets treated with an insect repellant. Their family planning research showed that it is possible to increase contraceptive use and slow population growth even in an impoverished, poorly educated population. This is especially important research since Navrongo is close to the Sahel, and the people there are similar to Sahelians in their preference for large families.

In 1995, the beginning of the Navrongo studies, the average woman had about 5 children. Fifteen years later, in 2010, that number had dropped to a bit over 4, both in the Navrongo control group and in the country as a whole. One of the interventions decreased the fertility further, to 3.7; a significant reduction. Now, a decade later, the fertility rate for the whole country is 3.7 children per woman. That group was ten years ahead of the rest of the country! This group combined specially trained community health nurses (as opposed to stationing them at a clinic or hospital) and “zurugelu”.

“Zurugelu” means “togetherness for the common good”, and was male-centered in the past. For a better explanation, I asked one of the investigators who had worked in Navrongo what “zurugelu” meant. Here is Dr. James Phillips’ reply:

“The zurugelu approach is a social engagement strategy that involves merging the organizational system of primary health care provision with the traditional system of social organization and governance. When gender problems were evident, we attempted to turn patriarchy on end by working with women’s social groups in ways that were traditionally dominated by men. Social events, termed “durbars”, were traditionally male events that were led by traditional male social leaders. To build women’s autonomy and roles, we worked with leaders to eventually have women’s convened and women’s led durbars. We also had gender outreach activities for responding to the needs of women. As such, the “zurugelu” approach was a gender development strategy.”

(A “durbar” is a meeting of men with their chiefs.)

It is interesting that neither community health nurses nor zurugelu alone had much effect on fertility. Even though the nurses educated women about family planning and supplied the necessary materials, fertility did not decrease significantly in the regions where they were introduced but didn’t have zurugelu. Nor did zurugelu alone have much effect by itself. It took both working together for the fertility to come down.

The need for both nurses and zurugelu is a very important observation. The statement has been made frequently that worldwide over 200 million women want to limit their fertility but don’t have access to modern contraception. Since the nurses provided that access, we know that access alone isn’t enough—at least in this group of people. Apparently tradition and paternalism were significant barriers to using contraception. It took zurugelu to change attitudes before people made the most of what family planning was available.

What difference did zurugelu make? This traditionally male function opened the eyes of men to the needs of women. Furthermore, the Navrongo programs strengthen the roles of women.

Now, back to my visit in Ghana. It was dusk as we were driving from Navrongo back to Nalerigu. We passed a straw hut with smoke emerging from its roof.

“Is it on fire?” I asked.

“No”, my host replied. “She’s just cooking the evening meal.”

Although there is much beauty in northern Ghana, and everyone I met was friendly and warm, my impression is that life is difficult. Now that child mortality is a fourth of what it was 50 years ago, people will benefit from smaller families as well as more education.

© Richard Grossman MD, 2022